The Wakizashi of Yagyū Renyasai: How the “Demon’s Cleaver” Was Born

The “Demon’s Cleaver”: the legendary wakizashi of Yagyū Renyasai

In the broad world of Japanese swords, few blades have managed to create such an aura of mystery and strength as the wakizashi called “Fūchinkiri Mitsuyo,” also known as “Oni no Hōchō” — the Demon’s Cleaver. Forged for Yagyū Renyasai, master of the Yagyū Shinkage-ryū school and central figure in the Owari lineage, this blade represents a captivating blend of craftsmanship, skill, and lore.

An uncommon warrior

Renyasai, the direct grandson of the renowned Yagyū Sekishūsai and a member of a prominent branch of the Shinkage-ryū school, was both a master of kenjutsu and a refined aesthete. A lifelong bachelor by choice, he lived entirely devoted to the path of the sword. In addition to his martial talents, he was an innovator in weapon design — creator of the Yagyū koshirae, unique tsuba, and even respected as a potter and landscape artist.

The blade’s creation

Tradition tells that Renyasai ordered his court smith, Hata Mitsuyo, to create the ideal wakizashi — one that could serve him when a long katana was unavailable, a common circumstance at a daimyō’s court or during formal visits.

After six failed attempts, Mitsushiro finally succeeded on the seventh try. To prove the blade’s quality, he cut through four fūchin (paperweights, typically made of stone – Editor’s note) stacked together. Renyasai, satisfied at last, accepted the sword: thus the Fūchinkiri Mitsuyo was born.

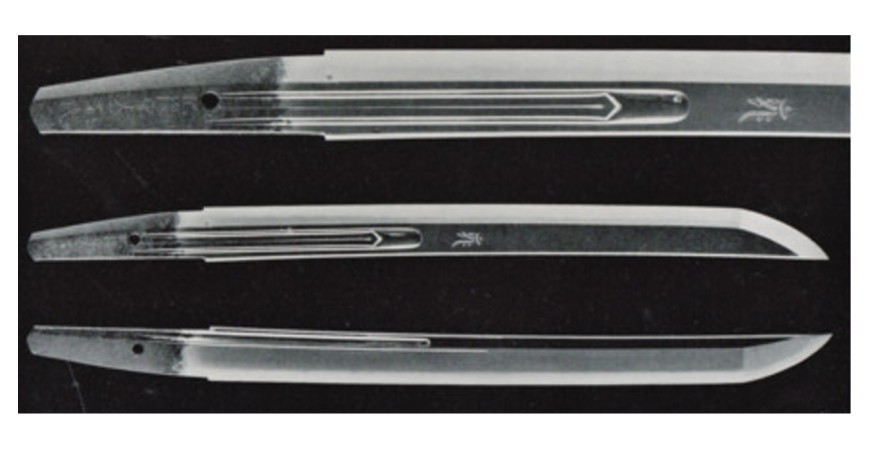

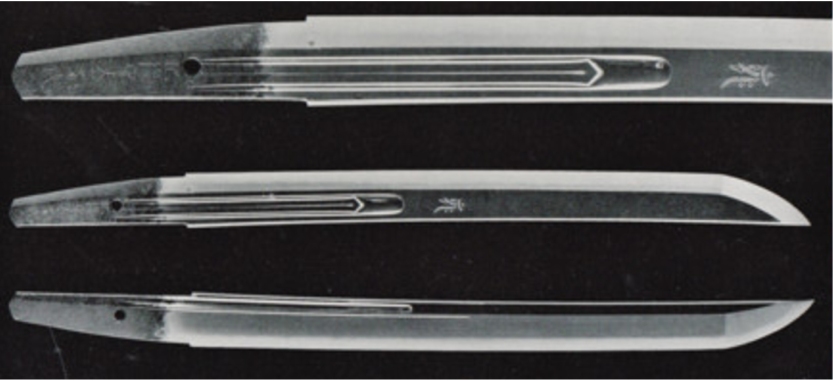

A weapon meant for actual combat

The wakizashi measures about 1 shaku 3 sun 6 bu (16.2") and has an asymmetrical construction: the omote side in kiriha-zukuri style, the ura in shinogi-zukuri. Its hamon (temper line) is suguha, and the hada (steel pattern) is a fine itame with many nie. Though short, the blade is solid and thick, featuring a horimono (engraving) of a ken inside the bohi on the omote side.

The Demon’s Cleaver

The nickname “Oni no Hōchō” wasn’t given lightly. One popular tale recounts that thieves broke into Renyasai’s chamber by night. Waking abruptly, he grabbed his wakizashi and struck each down with a single blow. The event became legend in the Owari domain, and the name of the blade spread quickly — so much so that replicas were eventually forged.

A symbol of samurai culture

In feudal Japan, it was always permitted to wear the wakizashi at one’s side, unlike the katana, which was often left at the entrance. This made the wakizashi extremely valuable — tactically and symbolically. In daily life, it was a samurai’s true line of defense. A common saying expressed it:

“The closer the weapon is to the body, the more refined and worthy it must be.”

Nevertheless, toward the end of the Edo period, the rise of shinai-based training and distancing from practical wakizashi techniques made them rare. Tragic events, like the death of Sakamoto Ryōma, who couldn’t get his katana in time during an indoor attack, show how dangerous it was to forget the practice of wakizashi kenjutsu.

A legacy that endures

Today, Yagyū Renyasai and his “Fūchinkiri Mitsuyo” remain cornerstones in the history of the Japanese sword — not only for the weapon’s technical quality, but for the ideal it represents: the perfect union of discipline, precision, and the warrior spirit.